Tim Dolby

This report covers the Kutini-Payamu (Iron Range) National Park on Cape York. Most of Cape York is an untouched wilderness dominated by open eucalypt woodlands and melaleuca forests, lowland rainforest, some wonderful heathlands, and coastlines. Cape York has recently been nominated for a UNESCO World Heritage listing for its globally significant landscapes, culture and wildlife. It is known for its rugged national parks, pristine waterways, secluded beaches, and rich Indigenous culture and rock art. The tip of the Cape York Peninsula, known as Pajinka in its First Nations name, is the most northern point on the Australian mainland. Cape York Peninsula is a vast area that has spectacular landscapes and a mosaic of ecosystems that supports extraordinary biological biodiversity. Savanna woodlands and spectacular lowland rainforest adjoin river catchments and wetlands. The integrity of the peninsula’s interconnecting ecosystems and their evolutionary links with New Guinea make it one of a kind. Cape York is certainly on the bucket list of most Australian birdwatchers!

Located on Cape York’s eastern side, Kutini-Payamu (Iron Range) National Park protects the largest area of lowland rainforest in Australia. The Cape York Peninsula was previously connected to New Guinea, so there is an interchange of flora and fauna that has left a rich biological legacy on the Cape York Peninsula. A visit to Iron Range gives you a window into the lowland rainforests of New Guinea. The rainforests are without doubt one of the most significant birdwatching sites in Australia; as a testament to this, in my book Finding Australian Birds: A Field Guide to Birding Locations (CSIRO), the list of key species in Iron Range is the longest of any Australian location. The Iron Range is certainly on the bucket list of all Australian birdwatchers.

I have been very fortunate to have visited Iron Range many times, heading up there as a professional bird guide, mostly as a leader for the excellent Bellbird Birding Tours. On these occasions, I use my existing knowledge to help others find the special birds of the area. The aim of this report is to share some of that knowledge and help you with your own trip to this remarkable part of Australia.

Trips to Iron Range are often done in association with trips to Cairns, Artemis Station, and Lakefield National Park; I talked about these spots in another trip report.

There is evidence of occupation of well over 30,000 years, and that history, that culture, and that tradition are in an unbroken line with people found in the area today. The Kuuku Ya’u (Kanthanampu and Kungkay) people are the traditional owners of Kutini-Payamu (Iron Range) National Park. Kutini is the Kuuku Ya’u name for the Southern Cassowary, while Payamu means rainbow serpent. I acknowledge the Kuuku Ya’u as the traditional custodians of this land.

Some introductory notes

Kutini-Payamu (Iron Range) National Park is around 750 km from Cairns and accessed via the Peninsula Development Road, the road that heads up the spine of Cape York. The roads are mostly dirt, but generally OK. Some can be a bit tricky, so 4WD is recommended. There are a few river crossings, crossable in most months except the summer wet months. Once in Iron Range, petrol is available at the supermarket in Lockhart River.

On my first trip, we hired an old Land Cruiser from a second-hand rental company in Cairns. After driving it around, we realised it was falling apart at the hinges. For example, part of my door handle came off the first time I opened the door. After getting a flat tyre, we discovered that the car didn’t have the appropriate wheel brace, so we couldn’t change it. Luckily, a passing 4WD helped us out. If we’d been in a more remote area, we would have been up sh… well, you know. So, as you do in a situation like this, we affectionately named her Bessie. This was a lesson learned. On my following trips, we always hired a new 4WD.

I was talking with a friend recently about the idea of riding a bike as an option for travelling around Iron Range. The idea is actually pretty good, as the distances you would need to ride are actually very manageable for cycling. You would need to allow more time for getting to key sites, and perhaps a day or two more for any itinerary. But, if you were a cyclist, it would be great fun, and you would certainly see many birds as you ride on the area’s roads. It might be also worth talking to Greenhoose (an accommodation option mentioned below) to get some bikes in, as a long term cycling option.

Another option is to fly into Lockhart River Airport. During the wet season, this is the only way to get there. Flights into Lockhart River are with SkyTrans Airlines from Cairns, and there is car hire in Lockhart River (although it’s been suggested to me that you should check that they have a spare tyre).

Note: you are not allowed to take alcohol on the flight in to Lockhart River, and there is no alcohol available any where in the region.

Food is available in Lockhart River, although you may want to stock up in Cairns before you go, and it is worth taking plenty of water. Portland Road has an excellent café called Out of the Blue. The food there is sensational—certainly the best seafood on Cape York. So, you might factor in a visit; I recommend contacting them before going. It is worth noting that there are strict alcohol restrictions in Lockhart River and surrounding communities (with fines as much as $75,000). This includes the cabins at Lockhart River Airport, but not Greenhoose and the campgrounds. You cannot buy alcohol anywhere in the region. So, if you want a drink, make sure you buy it in Cairns before you leave.

In terms of accommodation, on my first trip, I camped at Gordon Creek, There are also excellent camp grounds at the Rainforest Campsite, Cooks Hut, and Chilli Beach. When guiding, I tend to stay at either the Greenhoose (pronounce it as though you’re Scottish) or Iron Range Cabins at the Lockhart River Airport. Both are excellent. There is also some rental accommodation at Portland House in Portland Roads.

To give you an indication of what the weather is like, on my first trip I packed a sleeping bag and jumper; I didn’t use either for the entire trip. Most of my stays there have been between July and early November, when there is little rain and the mean temperature is around 30 degrees Celsius. On my last trip, however, the rain arrived early, and we had to make a quick dash to get out. Essentially, winter in Iron Range is pleasantly warm. If traveling in the summer wet season (November to April), it is wet, hot, and humid. Very wet, very hot, and very humid!

Brief overview of the birds

There are many parallels between the tropical rainforests of Iron Range and those of New Guinea, most prominently highlighted by the similarities in bird species. The main birding highlights are Red-cheeked Parrot, Papuan Eclectus Parrot (formerly just Eclectus Parrot), Palm Cockatoo, Yellow-billed Kingfisher, Chestnut-breasted Cuckoo, South Papuan Pitta (formerly Red-bellied Pitta), Fawn-breasted Bowerbird, Black-eared Catbird, Northern Scrub-robin, Trumpet Manucode, Magnificent Riflebird, Green-backed, White-streaked, Tawny-breasted, and Graceful Honeyeater, White-faced Robin, Frilled-necked Monarch, Black-winged Monarch, Yellow-legged (Flycatcher) Flyrobin, and Tropical Scrubwren! That’s a lot of highlights! If you add the Golden-shouldered Parrot and Black-backed Butcherbird, seen around Musgrave, that is 23 species whose Australian distribution is limited to Cape York! There is nowhere else in Australia quite like it!

Black-winged Monarch and South Papuan Pitta are only present in Iron Range in the summer wet season, arriving mid-November and leaving early April. As mentioned, unfortunately the roads into Iron Range are closed at that time of year. So if you wish to see South Papuan Pitta and Black-winged Monarch, you will need to fly into Lockhart River and hire a car. The same applies for Buff-breasted Paradise-Kingfisher, but these are relatively common around Cairns at that time of year. The wet season is also the best time for Black-eared Catbird. They tend to be extremely quiet at other times of the year and difficult to track down.

There is a whole bunch of other stuff to see in Iron Range. For instance, with luck, you might see Southern Cassowary (northern population), Spotted Whistling-Duck, and Red Goshawk, and vagrants such as Swinhoe’s Snipe. Most of the special birds you get around Cairns you also get in Iron Range! I’m thinking of birds such as Lovely Fairy-wren, Yellow-breasted Boatbill, Noisy Pitta, the monarchs, and fruit-doves. Some of these are easier to see at Iron Range than Cairns, such as White-eared Monarch. There are also the Cape York subspecies, such as Double-eyed (Marhshall’s) Fig-Parrot (ssp. marshalli), Marbled Frogmouth (ssp. marmoratus), Rufous Owl (small ssp. meesi), and Australian Brush-turkey (violet-wattled ssp. purpureicollis). So, the list of highlights for Iron Range is insanely good!

An overview of some of the plants of Iron Range

Cap York Peninsula is home to nearly a fifth of Australian plant species, despite only being 3 per cent of continental landmass. It includes more than 3,300 vascular plant species and 1,100 rainforest species. There is a strong biological connectivity between Australia and New Guinea that continues to evolve. The flora of Cape York representative of the global development of sclerophyll (hard-leaved) plants, including rare tropical heaths.

Kutini-Payamu (Iron Range) National Park is particularly diverse. The lowland rainforest are dominated by some spectacular trees. The giant Green Fig (Ficus albipila) grows to an amazing 35 metres, which is why it gets its alternative name, Abbey Tree. Aside from being an important food source for fruit-eating birds, they are the preferred breeding tree for Papuan Eclectus Parrot. While the Cape Fig (F. nodosa), Sandpaper Fig (F. opposita), and Opposite Leaf Fig (F. hispida) are all the favorite foods for the Double-eyed Fig-Parrot. The Blue Quandong (Elaeocarpus augustifolius) is a favorite food of Southern Cassowary. Lowland rainforests of Iron Range are an important habitat for Southern Cassowary, with many of the larger fruiting plants relying on them for seed distribution. The Leichhardt Tree (Nauclea orientalis) grows to around 30 metres. They bear clusters of fragrant flowers that develop into golf-ball-sized fruits. These fruits are edible and a valuable food source for First Nations people. They are also eaten by fruit bats and Southern Cassowary.

The Beach (Indian) Almond (Terminalia catappa) is an attractive large deciduous that occurs along the coast at Quintell Beach near Lockhart River. They have distinctive layered branches and edible nuts. It just so happens that Palm Cockatoo love these nuts, and will regularly visit the trees to feed, particularly early in the morning.

Another bird attracting plant is the Northern Laurel (Cryptocarya vulgaris). Their berries are a favourite of food sources for Trumpet Manucode, Magnificent Riflebird, Metallic Starling, Double-eyed Fig-Parrot, Red-cheeked Parrot, Southern Cassowary and the fruit-doves, and their flower attract a wide selection of butterflies. The seed of Australian Umbrella Tree (Heptapleurum actinophyllum) are spread by the same fruit-eating birds mentioned above, while its delightful red flowers attract nectarivores such as Tawny-breasted Honeyeater, Graceful, Yellow-spotted, and Green-backed Honeyeater.

Look also for the magnificent Black Bean (Castanospermum australe), a large tree prized for its colorful bicolored (red and yellow) flowers. Black Bean trees have large, albeit toxic, chestnut-like fruit. However, if treated, they can be edible. For instance, First Nations people prepared them by roasting pods, then leaching them with running water for several days, before pounding them into some flour for damper. The importance of Black Bean as a food source for First Nations people meant that the larger trees were seasonal gathering points, and the Black Bean tree featured in many First Nation song-lines, being a feature of directional travel.

The Bangalow Palm (Archontophoenix cunninghamiana) and Costate Palm (Hydriastele costata) are both striking to look at, as are the Corncob Pandana (Pandanus zea). In places the local bamboo, Iron Range (Black) Bamboo (Neololeba atra), form dense impenetrable thickets, usually near swamps. Far less appealing, Iron Range Wait-a-While (Calamus warburgii) vine has caught me off guard many times! Considered Vulnerable, it distribution is limited to Iron Range. Wait-a-While are also known as the Lawyer Palm because once they’ve hooked on to you, they won’t let you go.

One of the most intriguing plants of Iron Range is the epiphytic Ant Plant (Myrmecodia beccarii). They have a close relationship with ants, a butterfly, and a bird! The prickly, swollen stems develop natural hollows that act as nesting sites for ant species such as the Golden Ant (Iridomyrmex cordatus). In a symbiotic arrangement, the ants patrol the plant, removing any leaf-eaters. At the same time, the plant absorbs their excreta for nutrition. The Apollo Jewel Butterfly (Hypochrysops apollo apollo) lays its eggs on the Ant Plant. The butterflies eggs smell like ant eggs, so the ants carry the eggs inside the plant. The larvae then hatch, and they then feed on food begged from the ants or, indeed, eat ant larvae, or both. Finally emerging as a beautiful butterfly. The fruit of the Ant Plant is white and translucent and contains a single seed. The fruit and seed are then eaten by the Mistletoebird, who transport them through their digestive system to other trees.

Eucalypt woodlands comprise of around 60% of the region around Iron Range, with around 40% dominated by woodlands of Darwin Stringybark (Eucalyptus tetrodonta). Other eucalypts in the woodlands include Cape York Red Gum (E. brassiana), Molloy Red Box (E. leptophleba), and Large-fruited Red Mahogany (E. pellita).

For me, a real highlight of Iron Range is its wonderful heathlands—an area I would love to spend much more time investigating. It seems strange to go from tropical rainforest into heathland in a matter of moments, and with almost no sign of a gradient.

Over 200 different plants occur in the heathlands, and, in spring, the heath is covered in wildflowers. For me, the heath in Iron Range is reminiscent of the heathlands in southern Australia, such as in Tasmania and around Croajingolong. The more prominent heathland plants are the Black She-oak (Allocasuarina littoralis), as well as a nice selection of grevilleas.

One of my absolute favourites plants is the Golden Parrot Tree (Grevillea pteridifolia). It has wonderful orange flowers that stand out as you move through the heath. Along with the Silver Oak (G. parallela), their nectar-rich flowers are an important food source for birds such as the White-streaked Honeyeater and Rainbow Lorikeet. First Nations people soaked the nectar-rich flowers in water to make a sweet drink, while I like to dip my fingers in the flower’s nectar. It’s yum!

One plant, the Mount Tozer Prostanthera (Prostanthera tozerana) is a species whose distribution is solely limited to Mount Tozer. First formally described in 2015, look out for it, it is a form of mint-bush that has lovely purple flowers.

The banksia species Iron Range is the Tropical Banksia (Banksia dentata). It is the only banksia species found outside Australia, and was the first banksia collected by Joseph Banks on the Endeavor in 1770. producing copious amount of nectar, it is a significant bird, mammal and insect attracting tree.

The Northern Forest Grass Tree (Xanthorrhoea johnsonii), widespread in the heath, is another bird, mammal and insect attracting tree. If you find one of these flowering, it is always worth investing, as it may be surrounded by butterflies and native bees. Broombush (Jacksonia thesioides) have delightful pink flowers, while the Broom Bogrush (Schoenus sparteus) is a sedge that grows about a metre high. Look closely for terrestrial orchids, such as the Cinnamon Orchid (Corymborkis veratrifolia). Look also for epiphytic orchids such as the Fragrant Tea Tree Orchid (Dendrobium trilamellatum), Cape York Vanda (Vanda hindsii), and beautiful purple Cooktown Orchid (Dendrobium bigibbum), the floral emblem of Queensland.

Low open Melaleuca paperbark woodlands and swamplands cover around 10% of the habitat, with species such as Silver Tea-tree (Melaleuca argentea), Broad-leaved Tea-tree (M. leucadendra), and in the swampy areas and around wetlands, Swamp Paperbark (M. quinquenervia) and Swamp Tea-tree (M. dealbata). For me, an absolute star plant of the wetter areas of Melaleuca woodland is the Tropical (Swamp) Pitcher Plant (Nepenthes mirabalis). Its Latin name, mirabalis, means ‘wonderful’. They surely are! Seeing them for the first time was a impressive sight. Some were quite large, about the size of drinking glass. They were also quite variable in colour, some red, others green. Many of the pitcher plants were being protected by Green Ants (Oecophylla smaragdina). I thought this somewhat ironic. Pitcher plants are, of course, carnivorous, and have a modified leaf known as a pitfall trap that contains liquid. This liquid both kills and digest insects that fall into the trap. When I investigated this digestive liquid, the predominant prey of the Tropical Pitcher Plant was the Green Ants!

Green Ants themselves are quite fascinating. They will be familiar to anyone who’s either lived or travelled in northern tropical Australia. They build a colonial leaf nest in trees. They are aggressive towards any perceived threat to their nests. Swarming, and then biting anything or anyone, to ensure an intruder knows exactly who’s the boss. I have known many people have been covered with Green Ants when brushing up against a bushy tree. The resulting hopping and slapping is known as the ‘Green Ant Dance’, a sight to see. In some cases, you are forced to take all your clothes off because they have gotten under your trousers. Indeed, I have had to do this myself! Luckily, there was no one around to see me perform the Green Ant Dance!

There are well over twenty species of mangroves, with a good spot to see them being the township of Portland Road. Mangroves generate a range of responses; some people love them and others hate them. Birdwatchers tend to love them because they attract birds that only occur in mangrove environments. These days, mangroves are much more appreciated because of the ecological and protective benefits they give to marine, coastal, and estuarine environments.

Here is a brief selection of some of the mangroves that grow in the region: River (Black) Mangrove (Aegiceras corniculatum), whose bark was used as a fish poison; White Mangrove (Avicennia marina) has the widest distribution of any Australian mangrove (for instance, its distribution extends as far south as Victoria); the timber of Spurred Mangrove (Ceriops tagal) is strong and is preferred as firewood; the Wrinkle Pod Mangrove (Cryptocarya vulgaris) is a small mangrove that tends to grow on the landward side of mangroves; finally, the Milky Mangrove (Excoecaria agallocha) has an alternative name, the Blind-Your-Eyes Mangrove, which refers to the toxic properties of its latex (the milky fluid in some plants) that come into contact with your eyes. Several of Captain Cook’s men were blinded when they were sent ashore to get firewood. Don’t worry, the blindness is only temporary. Like River Mangrove, the dried powdered leaves were used to kill fish.

Finally, the Beach (Coastal) She-oak (Casuarina equisetifolia) seem like a good plant to finish of this section. It is also known as the Whistling Pine, because of the noise that is made as the wind passes through its leaves. She-oaks, the Casuarinas, are an unusual plant family as they have separate male and female plants. Each year the males turn a dusky red colour as they release pollen, while the females have small red flowers and lots of seed cones.

WHERE TO SEE THE BIRDS

Claudie River Bridge and adjacent grassland

So, now to the birding sites!

When bird guiding in Iron Range, the Claudie River Bridge is one of the first places I visit i.e. on the first morning. It located on Portland Roads Rd (such a great name for a road and, these days usually abbreviated to Portland Rd), it is just west on the intersection with Lockhart River Rd. This intersection is known as Three Ways (or, sometimes, the Triangle).

My aim for the morning is to start birding at the bridge, then continue to birdwatch locations as I move east. Doing this, until I have reached somewhere like the Gordon Creek Bridge. The idea behind this is, after the first morning you know what rainforest birds you have seen, and what you have missed. After that you can specifically target the bird species you still need to get.

I find the Claudie River Bridge a good spot to just hang around and birdwatch, perhaps for half an hour or so (longer if you are in no hurry). You can stand on the bridge itself, looking up and down this wonderful river (of course, watching out for cars as they cross the bridge), and walk up and down the road a bit. There is usually quite a lot of activity. I found it a particularly good spot for Frilled-necked Monarch. Usually sedentary, there is often a pair on the east side of the bridge. The plumage of the Frilled-necked Monarch is quite distinctive. Like the Pied Monarch, they have a wonderful white ruff (the frill) that fluffs right up when excited. It is delightful to see. They are quite active, regularly making buzzing cicada-like calls.

The Claudie River Bridge is also a good for Chestnut-breasted Cuckoo, whose rich chestnut colours and yellow eye-ring make it stand out and tends to be a bit higher up in the canopy. Listen for their trilling call, it’s somewhat similar to a Fantailed Cuckoo.

At the Claudie River Bridge I have also seen Tropical Scrubwren, Yellow-breasted Boatbill, Spectacled Monarch, Lovely Fairy-wren, White-browed Robin, Yellow-spotted, Graceful, and Tawny-breasted Honeyeater, while Fairy, and Large-billed Gerygone can be seen flittering around the southern side of the bridge. The rainforest to the east can be good for Magnificent Riflebird and Trumpet Manucode. In the wet, this spot is good for Black-winged Monarch and South Papuan Pitta.

A walk into the rainforest just north of the bridge produced nesting Green-backed Honeyeater, as well as White-eared Monarch and Yellow-legged Flyrobin. It is in this area that I once disturbed a nest of Paper Wasp. Anyone who has done this before will know exactly what I am about to say. I sustained several extremely painful stings, including one on the ear, sending me into a mild state of panic! I rushed up a nearby ridge, straight into some Wait-a-while. Under the circumstances, this seemed like a mild distraction when compared to stings of the Paper Wasp! Fortunately for me, I managed to break free, and the pain from the bites disappeared after about half an hour or so.

Just west of the bridge there is a large open grassy area. This is a good spot for Golden-headed Cisticola, and, although I have not seen them there, I am sure it would be good for Zitting Cisticola (a bird not yet officially recorded in Iron Range). Because the grassland is a big open space bordered by rainforest, it is a good space to see birds flying over the field. I have found it a good spot for Palm Cockatoo, usually seen as a dark silhouette in the distance with broad wingbeats, as well as Papuan Eclectus Parrot and small parties of Red-cheeked Parrot.

The Papuan Eclectus Parrot just are a conspicuous bird. You usually see them in groups of three—perhaps a female at the front, being followed by two males—making loud, ear-splitting screeches as they fly across the sky. Few species have puzzled scientists more. Papuan Eclectus Parrot have the distinction of being the most sexually dimorphic of all the parrot species, at the same time as exhibiting reverse sexual dimorphism. The males are a vivid emerald green, while the females are deep, bright red. They are so different in colour that it wasn’t until 1874 that they were considered to be the same species.

Other birds I have seen flying over the grassland were Australian Swiftlet, Tree Martin, Tree Martin, Pacifica Baza, and Grey Goshawk (both white and grey morphs seem to be evenly present in Iron Range), and it is the only place I have seen Red Goshawk in Iron Range, a single bird flying over the grassland, heading north. It is also a spot I have seen Southern Cassowary. Always a tremendous sight, it walked away into the rainforest fringe on the west side of the grassland.

Three Ways (The Triangle)

Three Ways (or the Triangle) is the name of the intersection between Portland Rd and Lockhart River Rd (from there you can either head east to Portland Road, south to Lockhart River, or west out of Iron Range, hence Three Ways). Another name for it is the Triangle, because the road here is triangular. After stopping off at the bridge, I usually stop and birdwatch just east of this intersection, where Portland Rod runs close to the West Claudie River. It is a good spot for Tropical Scrubwren, and I have also seen Superb and Wompoo Fruit-Dove, Tawny-breasted and Green-backed Honeyeater, Rufous Shrike-thrush, Magnificent Riflebird, White-faced Robin, and Yellow-legged Flyrobin.

It is interesting to note that the grasslands here are apparently the spot where ‘Operation Blowdown’ was conducted in 1963. It was a large explosive test to simulate the effects of a nuclear weapon on tropical rainforests, hence the grassy areas; I remember Les Hiddens visiting the site in an episode of The Bush Tucker Man. Like the grasslands near the bridge, you occasionally get flyovers of Palm Cockatoo, Papuan Eclectus Parrot, and Red-checked Parrot. Red-cheeked Parrot are best seen in the morning, usually seen in fast-flying, noisy, conspicuous pairs. They seem to like watercourses as well as preference for the rainforest edge.

Rainforest, Cooks Hut and Gordon Creek camping areas

For rainforest species, the main areas for birding are along Portland Rd., from the Rainforest campground in the west, past Cooks Hut campground, to Gordon Creek campground in the east. One of the more productive approaches to locating rainforest bird species is to birdwatch along the rainforest edges, i.e., birdwatch along Portland Rd. itself. I have found birdwatching immediately east of Cooks Hut particularly good, particularly for Trumpet Manucode, Yellow-billed Kingfisher, and Green-backed Honeyeater.

Trumpet Manucode are a wary species in the bird-of-paradise family, occurring more often than not in the upper stratum of the rainforest. As a result, they can be tricky to see as they feed on the rainforest fruits. Here is one way I tend to find them. Every now and then they’ll let out a loud and unique SKOWP sound, likened to a low-pitched trumpet (hence Trumpet Manucode). You can hear it from some distance. Once heard, head directly to that spot and search for the bird. More often than not, however, you will need to wait until they make the call again. This can be a delay of perhaps five minutes. It is only when they make their second call (or even a third call) that you might locate them. Look for a glossy, iridescent blackish-blue bird that’s slightly bigger than a Spangled Drongo.

The trumpet part of the Trumpet Manucode’s name is fairly self-evident (as mentioned above), but where does the word Manucode come from? Manucode probably comes from the Indonesian word manuk dewata, which means ‘birds of the gods’. Indeed, until the 1800’s, ‘Manucode’ was the generally used word for all the bird-of-paradise. As Susan Myers writes in her excellent book The Bird Name Book: A History of English Bird Names:

It wasn’t until the 1800s that the appellation bird-of-paradise was adopted and the name manucode came to be assigned to arguably the most boring representative of the family.

So, being a uniform iridescent black colour, you might ask why is the Trumpet Manucode boring when compared to other bird-of-paradise. (Well, you may not have asked this question, but I have). Trumpet Manucodes are sexually monomorphic, i.e., both sexes are similar in appearance. This is unusual in the bird-of-paradise family. This feature is linked to the fact that Trumpet Manucodes are monogamous. As a consequence, there is no need for the elaborate looks and behavior of some of the other more strikingly coloured birds-of-paradise.

With colours dominated by yellow, orange, and blue-green, the Yellow-billed Kingfisher is so different from other Australian kingfishers. Despite its colour, it can be hard to locate. So, like a lot of rainforest birds, it is best located by its call, a loud musical trill that is unlike any of the other Australian kingfishers. They can sit still under the canopy for a long time, sometimes a very long time. For instance, I remember the first time I saw a Yellow-billed Kingfisher. Out of the corner of my eye, I had noticed a bird fly into a tree out and was pretty sure it was the kingfisher. So, my technique for seeing it was to simply wait under that tree until it flies out. After what seemed like hours, a Yellow-billed Kingfisher flew out of the tree. Bingo! Lifer pie!

Another bird to look for here is the magnificent Magnificent Riflebird. They are velvety-black bird-of-paradise with a large iridescent, almost turquoise-coloured, triangle-shaped breast shield. This look is probably how they got the name ‘Riflebird’, because they resembled the colours of the British Rifle Brigade. They are usually quite high in the canopy, and easily the best way to find them is by their call. It makes an extremely loud wee-ee-oop or wep-weep, likened to wolf-whistle, that reverberates through the rainforest! It’s a call that contrasts markedly with the rasping calls of the Paradise and Victoria’s Riflebirds. The most often seen view of the Magnificent Riflebird is of it darting across the road, from one section of rainforest to another.

Other birds to look for in the rainforest near the camp grounds include Papuan Eclectus and Red-cheeked Parrot, Double-eyed (Marshall’s) Fig-Parrot, Wompoo, Rose-crowned, and Superb Fruit-Dove, Chestnut-breasted Cuckoo, Spangled Drongo, Yellow-breasted Boatbill, Spectacled, Frill-necked, and White-eared Monarch, Tropical Scrubwren, Rufous Shrike-thrush, Rufous Fantail, Tawny-breasted Honeyeater, Grey Whistler, Black-winged Monarch (summer), Oriental Cuckoo and White-faced Robin. So, this area of rainforest is a good spot!

While most of the rainforest birds are best seen near the edges, White-faced Robin seems to prefer the denser habitat inside the rainforest. I have found walking along the very beginning of the Old Coen Track at the Rainforest Campground (the section the Claudie River) is a good spot for them, often perch on the side of a tree, or vine, as robins generally do, dropping to the ground to snap up an insect or two. They are usually quiet, so it is worth moving slowly along the rainforest tracks to see them. They also occur along the small track leading north behind the Cooks Hut Campground. One of these tracks leads to the toilet block.

Another bird you sometime see behind the Cooks Hut Campground is Norther Scrub-robin. They are best seen by entering the gallery rainforest and search for movement on the ground. In summer, this area is also good for South Papuan Pitta, feeding in the leaf litter.

I have camped at both Gordan Creek and Cooks Hut campsites and, on both occasions, there were several Spotted Cuscus in the trees bordering the campsite. They seem particularly numerous at Cooks Hunt, and you can occasionally see them in the middle of the day in the larger trees in the campsite itself. With their flat face, forward-looking eyes, and tiny ears, Spotted Cuscus give me the impression of being a monkey. However, in terms of their movement, they are more like a sloth, being Australia’s slowest possum. Typically solitary, it is worth noting that only the male has spots. The Southern Common Cuscus, which is also found in Iron Range lowland rainforests, is similar but distinguished by the dark strip that runs down its back.

The Gordon Creek campsites are bordered by riverine rainforest. White-faced Robin can be a campground bird, frequently clinging sideways on tree trunks, as robins tend to do. In the afternoon, this campsite proved to be a good place for Green-backed Honeyeater, most often seen as a single bird. Nearly all of the Australian observations of Green-backed Honeyeater are made in the rainforests of Iron Range. The campsite is also a good spot for Yellow-legged Flyrobin. An uncommon species, they are often located by their distinctive calls, a short five-second trill (somewhat like the trilling call of the Yellow-billed Kingfisher). They seem to prefer the margins of the rainforest.

Around the campground you should also see a few Australian Brush-turkeys as they hassle each other and any Orange-footed (Megapod) Scrubfowl that gets in their way. The Australian Brush-turkey here are the violet-wattled subspecies, purpureicollis. The nominate subspecies lathami further south has a bright-yellow wattle. There is a nice little walk at the campground that leads down to the creek, a good spot for Chestnut-breasted Cuckoo, Trumpet Manucode, White-faced Robin, Frilled-necked Monarch, and Tropical Scrubwren.

Double-eyed Fig-Parrot are sometimes seen feeding in fig trees further down Portland Rd, just after the Gordan Creek Bridge. This bridge, like the West Claudie River Bridge, is a good place to just hang out and birdwatch. For example, from the bridge I have seen Yellow-billed Kingfisher, Red-cheeked and Papuan Eclectus Parrot, Black-eared Catbird, Magnificent Riflebird, Yellow-breasted Boatbill, Yellow-legged Flyrobin and Green-backed and Tawny-breasted Honeyeater. Tawny-breasted Honeyeater are a quite a large honeyeater with a large downcurved bill. To me the Tawny-breasted Honeyeater call sounds like the ‘rusty bicycle wheel’ call of the Large-billed Gerygone.

At night, spotlighting the road between Rainforest, Cooks Hut, and Gordon Creek campgrounds is probably the best way site for Marbled Frogmouth, Large-billed Nightjar, and Rufous Owl, and there is a chance of Red-necked Crake, with one calling while I was spotlighting the last trip I made there.

When spotlighting along Portland Rd look for nocturnal rainforest mammals. I have seen Spotted Cuscus, Giant White-tailed Rat and Cape York Melomys. While, if you are lucky, Sothern Common Cuscus (not that common), Stiped Possum, and Long-nosed Echymipera (formerly the Rufous Spiny Bandicoot), Cape York Rat and Cinammon Antechinus are all possible. The likely bats around along Portland Road are Eastern Horseshoe Bat, Fawn Leaf-nosed Bat and Large-eared Horseshoe Bat.

Cinnamon Antechinus is another mammal of the mesophyll rainforest of Iron Range. They breed in September, when the males become active. Looking for a mate, they extend their activities into the day, which is when you might see them scurrying across a road. After continually trying to mate for over a month, the males become exhausted, and by mid-October all the males are dead! So, after that, only female Antechinus exist, until they give birth to their first litters in late October and November. That is such an interesting life history!

The Bare-backed Fruit Bat and the much smaller Fawn Leaf-nosed Bat are among the common bats you will see along Portland Rd. You can distinguish the Bare-backed Fruit-Bat due to the distinctive flapping noise they make as they hover in mid-air.

There is also a chance of some good reptiles, such as Green Tree Python, a spectacular-looking python whose Australian distribution is essentially limited to the rainforests of Iron Range. The adults are a vivid emerald green, while hatchings (to around the age of 1 year) are yellow or brick red. They are sometimes colloquially called ‘green gold’ because they are very hard to find, so for ‘herpers’ (reptile enthusiasts), finding one is like finding gold.

You might also see Scrub (Amethystine) Python (it can reach 5 metres in length), Northern Tree Snake (fast and agile snake, and one of the more common snakes in the rainforest), Brown-headed Snake, Slaty-Grey Snake, Northern Carpet Python, Spotted Python (they’re the ones that hang out near near caves hunting bats in mid-flight!) and Black-headed Snake (who eat other snakes, including the venomous ones!).

Another very special reptile of Iron Range is the Canopy Goanna, found nowhere else in the world. Living in the rainforest, it uses its tail like a Spider Monkey, curling it around a branch of a tree like a fifth limb. It has a very restricted range of possibly less than one hundred square kilometres. First described as a species in 1985, there seems to be little information on this monitor, so could possibly do with a bit more research. Also look for Spotted Tree Monitor, Yellow-spotted Monitor, and Giant Tree Gecko; the latter distributions are limited to northern Cape York.

Another good area of habitat is along the track going down to the Claudie River at the Rainforest Campground. This is the eastern end of the Old Coen Track. White-faced Robin occurs along this track, as do Pacific Emerald Dove, and the river is to be a good place to see Frilled-necked Monarch, Red-cheeked Parrot, and Papuan Eclectus Parrot. It is also a good spot for Black-eared Catbird. They are notoriously difficult to see outside of the summer period, remaining silent and often feeding high in the rainforest canopy.

Here’s a bit of an aside. Once I camped at the Cooks Hut with two clients. They were a couple; she was an American doctor from New York and great fun, while he was a well-known Costa Rican bird guide. They had specifically asked to camp for a few days in Iron Range, so I packed a couple of small tents, some sleeping bags, etc. Once we arrived at Cooks Hut, I got the tents out of the car and said, “Here’s your tent. If you need any help, please let me know.” He, the Costa Rican bird guide, looked down at the tent, looked up at me, and then kicked the tent, saying, “What the F#@k is this!?” Naturally I was a bit surprised by this. I assumed a Costa Rican bird guide would know what camping is. Apparently not, his idea of camping was what we would call ‘glamping’ (quite common in Costa Rica). He assumed there would be a cabin-like tent, accompanied by a cook providing our food and a nice cold bottle of champagne on ice! (I’ve slightly exaggerated the champagne bit, but you get the picture.) Eventually he settled down and I set up his tent. Needless to say, we did not camp again. He was, in fact, quite a nice guy and good birder but had a habit of losing it a bit – something his wife had actually warned me about before the beginning of the trip. Indeed, she said they couldn’t do group tours because he’d always get in a fight with the other clients. At the end of the trip, as a present, he gave me a large bag of Costa Rican coffee that came from his local village. His wife was amazed, “He’s never done anything like that before!” So, I must have done something right!

Old Coen Track (Eastern End)

Around 5 kilometres in length, the Old Coen Track starts at the Rainforest Camping Area, heading west towards until it ends up at the site mentioned below. About 200 metres down the track you come to a spot that you will need to cross the Claudie River. Here you can either take your shoes off and wade across (it’s only about 15 metres through shallow water), or you can see if you get across via a fallen tree or two. I tend to walk a kilometre or two along the track, and then head back. (You can do the same thing from the other/western end).

The track takes you through some nice lowland rainforest and dry eucalypt woodland. It is a pleasant, well-marked track (don’t forget to take water) and pretty birdy in places, so it is worth doing if you have time. It’s a good spot for Papuan Eclectus Parrot, who like the trees along the path, as well as Red-cheeked Parrot, Pacific Emerald Dove, Northern Scrub-robin, Yellow-legged Fly-robin, Green-backed Honeyeater, Grey Whistler, Magnificent Riflebird, Yellow-billed Kingfisher, Lovely Fairy-wren, and, in summer, Black-winged Monarch.

Old Coen Track (western entrance) and along Portland Rd here.

Another good area of edge habitat is along the western end of the Old Coen Track. A walk west along the Old Coen Track is also worth doing, with most of the rainforest species possible along here. As mentioned, the habitat is a nice mix of open woodlands and lowland rainforest. It is 5 kilometres one way. I have found it good for the Black-eared Catbird, the fruit-doves, Wompoo, Superb and Rose-crowed, Chestnut-breasted Cuckoo, Tropical Scrubwren, White-eared and Frilled-necked Monarch, and White-faced Robin.

A focal point of walking this track used to be the Smuggler’s Tree, a large Green Fig (Ficus albipila) tree that was an important breeding tree for Papuan Eclectus Parrots. Its name is derived from the fact it used to be raided by bird traders for nestlings in the 1950s. Unfortunately, it has since fallen down. It used to be an incredibly majestic tree. Robert Heinsohn, one of the first researchers into Papuan Eclectus Parrot behaviour, wrote about the Smuggler’s Tree as such:

In its various hollows, it supported 17 Eclectus Parrots distributed among three different breeding groups, two pairs of Sulphur-crested Cockatoos and roosting cavities for bats inside its trunk. Its crown is decorated with a magnificent colony of Metallic Starling with their multitude of nests that hang from the upper branches. Preying on all these creatures is a resident pair of Grey Goshawks, and a large Slaty-grey Snake haunts the ground below, waiting for the starling chicks to fall. When they are all at home, the 12 male and five female Eclectus Parrots light up the branches like a Christmas Tree.

It is such a shame the Smuggler’s Tree isn’t still standing! As part of Robert Heinsohn’s research, he found that female Papuan Eclectus Parrots refuse to leave their breeding hollow even after their chicks have fully fledged and left the nest. They will return every day to make sure that no intruders have usurped it. They defend the hollow from others; regular scuffles break out and they even fight to the death to defend their precious nests. They do this because there is always a shortage of appropriate breeding hollows. The shortage of breeding hollows is in fact the reason for the different colour scheme between females (vivid red) and males (vivid green). As a rule, all hollows are situated in bright light, so the females, sitting at the entrance of their hollow, glow like a bright red beacon, stating that ‘This hollow is taken!’. Males, on the other hand, are green because green is a good camouflage colour, blending in to the greenness of the rainforest.

Some of the best birding at the western end of the Old Coen Track is along Portland Rd itself. This is an edge zone area, an ecotone between lowland rainforest and woodland, and it can be rich in birdlife. The rainforest on the south side of Portland Rd is particularly good for Northern Scrub-robin. Extremely shy, you may have to walk in to the rainforest to see them as they bounce around in the leaflitter. Northern Scrub-robin have always intrigued me. Its closest cousin, the Southern Scrub-robin, occurs three thousand kilometres away. That’s a long way away! They also have extremely different habit preferences; Northern Scrub-robin Robin likes rainforests, while Southern Scrub-robin prefers mallee and dry woodlands. So how are they linked?

Looking into the rainforest along this section of Portland Rd I have also seen Trumpet Manucode, Magnificent Riflebird, Graceful, Tawny-breasted, and Yellow-spotted Honeyeater, while Palm Cockatoo, Papuan Eclectus and Red-cheeked Parrot and Double-eyed Fig-Parrot regularly flyover.

West Claudie River Rainforest

If you head west along Portland Rd, there is a tremendous area of rainforest beside the West Claudie River—it is around 6 km from Three Ways—and it is the first section of rainforest you come to when entering Iron Range from the Peninsula Development Rd. Along this section of road was the very first place that I birdwatched in Iron Range. I have great memories of this spot, as it was my first introduction to the rainforest birds of Iron Ranges. It was like being a kid in a candy store and not knowing which candy to eat first. There were so many fantastic new birds to see; there was a dilemma about which way to look! I remember our conversation going something like this:

“Look, there’s a Trumpet Manucode and another (skowp!). Hear that, one just called in that tree! There, a Magnificent Riflebird (wee-ee-OOP), it also just called. Papuan Eclectus Parrot overhead, wow! Look there, Three Red-cheeked Parrots overhead! White-eared Monarch in that large fig tree, there! Hey, that’s a Palm Cockatoo calling!”

And, so, it went on! Wompoo, Superb Fruit-Dove, Frilled-necked, and Spectacled Monarch, Double-eyed Fig-Parrot, Graceful, and Tawny-breasted Honeyeater! A pretty special spot of rainforest.

Where to see White-streaked Honeyeater

This species deserves its own section in this report. This is because it can be a very tricky bird to find, especially if you don’t know the right place to look. Unless you specifically target it, it is often one of the last of the special Iron Range birds that birders see (or not see, in some cases). Fortunately, I can recommend two spots to see them (see below). Unlike most of the other birds restricted to the Cape York Peninsula, White-streaked Honeyeater do not occur in New Guinea. I have found them a restless honeyeater, rarely sitting in one place. They are also nomadic, relying on flowering trees and scrubs, such as the as the Orange Parrot Tree, for food.

East of Three Ways (The Triangle)

On the way to Portland Road, you pass through some excellent areas of heathlands. This habitat is perfect for White-streaked Honeyeater. I usually stop near an old abandoned truck on Portland Rd. around 9 km west of Three Ways (3.5 km west of the Gordon Creek campsite). Here you look and listen for White-streaked Honeyeater either side of the road—you can easily walk into the heath here if you need to. Other birds here are Leaden Flycatcher, Helmeted Friarbird, Dusky Honeyeater, and Grey Shrike-thrush.

The rare Chestnut Dunnart has also been recorded in the heathland here, although the last documented record (in a research pitfall traps) being in 1993. More recent camera trap photos have been made near Bamaga near the Tip, and astonishingly one was captured at Blackbraes National Park west of Townsville in 2003, a 1,000 kilometres south of its previous known range.

West of Three Ways (The Triangle)

The second is a creek around ~15 kilometres west of Three Ways (~4 km west of the Mt Tozer Lookout). Here there is a roadside pull-in on the north-west side of the creek (just after the culvert) and is essentially the only place you can pull-in along this section of the road. This spot is outside the national park. White-streaked Honeyeater occur here in the heathy scrublands, particularly on the south side of Portland Rd.

The other special thing about this site is the presence of carnivorous Tropical (Swamp) Pitcher Plant (Nepenthes mirabilis). Large numbers of them are scattered across the ground on the south side of Portland Rd., particularly in the slightly damp areas. They are simply spectacular!

White-streaked Honeyeaters are also occasionally seen the Mt Tozer Lookout, which is a particularly good spot for heathland wildflowers.

Portland Roads township

The township of Portland Roads is a tiny (much smaller than I thought) but welcoming and an excellent birding spot. Rose-crowed Fruit-dove and Pied Imperial Pigeon regularly fly across the inlet to roost in the mangroves on the left side of town. In the town’s gardens, Usually see Large-billed Gerygone, Sahul Sunbird, Varied Triller, and Green Oriole, and Varied, Graceful, Tawny-breasted and Yellow-spotted Honeyeater, and few Double-eyed Fig-Parrot.

The inlet in front of the town can be productive, particularly at low tide and the mudflats are visible. Indeed, when visiting Portland Roads check the tide charts. At low tides at Portland Roads, you can quite easily walk out to the seaside of the mangroves. Look on the mudflats for Beach Stone-curlew, Whimbrel, Common Sandpiper, Grey-tailed Tattler, Pacific Reef Egret, Striated Heron, and Torresian Kingfisher.

Birding the mangroves here can be really rewarding. There are stands of tall mangroves that, as mentioned above, can be accessed at low tide from the beach, i.e., walking out and around to the seaside of the mangroves; so it is worth checking the tide charts as to the best time to visit the mangroves. Alternatively, just walk west along the Esplanade, birding the mangroves along there. Some of the mangrove species I have seen here are Mangrove Robin, Torresian Kingfisher, Shinning Flycatcher, and it is a good spot for Rose-crowned and Superb Fruit-Dove, Torresian Imperial-Pigeon, Helmeted Friarbird, Large-billed and Fairy Gerygone. It is also the only place I have seen White-browed Robin in Iron Range. Interestingly, I have also had great views of Palm Cockatoo in eucalyptus woodlands just north of the mangrove, so listen out for them.

While I’ve not seen them, keep a lookout for other mangrove specialists such as Mangrove Golden Whistler, Red-headed Honeyeater, and Yellow White-eye, which have all have been recorded there. Ashy-bellied White-eye is also a possibility. Along with Mangrove Golden Whistler, they are regularly seen at Wuthara (Forbes) Island, just 40 kilometres of the coast from Portland Roads.

Standing on the small breakwater (a former Jetty) in the town’s north, you can usually add a few seabirds to your list. Here I have seen Lesser and Greater Frigatebird, Brown Booby, Common Noddy, Lesser Crested, and Bridled Tern feeding out at sea. While, at night, if you shine your spotlight into the water, you can see the eye-shine of the Saltwater Crocodile around 20 metres from the beach. And there can be plenty of eyes, which explains why swimming is not a good idea at Portland Roads.

Portland Road is a particularly good place for seeing Fawn-breasted Bowerbird, with a good spot to look being the scrubby eucalypt woodlands behind the mangrove on the north side of town. Start your search from a little picnic area around 300 metres west of the township. It is worth listening out for their distinctively metallic churring, often made near their bower.

Around 1 kilometre before you get to the township of Portland Roads, a short track leads east to a spot known as the Gravel Pits. This has become a reliable place to see Spotted Whistling Duck, although you may need to visit several times to see them. There are also usually a few Radjah Shelduck, Pacific Black Duck, and Grey Teal there as well.

At night, Portland Roads is a good spot for Large-tailed Nightjar. Listen for their repeated, “tok tok tok” call. At night, Bare-backed Fruit Bats also feed in the gardens in the town. Again, listen to the noise of their wings beating as they fly from tree to tree, looking in any fruiting and flowering trees.

Here’s a recommendation. Whether staying or visiting Portland Road it’s worth eating at the Portland Road café the Out of the Blue (mentioned above). On my first visit we regularly ate lunch and dinner at the café, enjoying fish and chips, prawn tempura, calamari, and for lunch prawn roles! While eating dinner a bonus was listening to Large-tailed Nightjar, a distinctive donk, donk, donk. We also saw what looked like Bare-backed Fruit-Bat, feeding in the gardens in the front of the café.

Lockhart River Treatment Plant

One of the best birding sites at Lockhart River is the treatment plant. To get there, from Lockhart River, head down Piiramo Rd. towards Quintell Beach, and after about 500 metres turn down Kuttini Street for around 300 metres, with the treatment plant on your right.

This treatment plant is an excellent series of ponds. In terms of waterfowl, there are usually a few Magpie Geese, Radjah Shelduck, Green Pygmy-Geese, Black Duck, and Grey Teal, and, in recent times, it is a go-to place to see Spotted Whistling-Duck, with occasional groups of over 20. A creek runs north of the pond; they are occasionally there. On or around the water there are usually a few Pied Heron, Cattle Egret, Australasian Grebe, Comb-crested Jacana, Masked Lapwing, and the causeways can be good for summer waders such as Pacific Golden Plover, Sharp-tailed and Common Sandpiper. In spring and summer there are usually a few Latham’s Snipe around, while in September 2009 my group saw a Swinhoe’s Snipe—so always be vigilant and have your camera ready.

The grassy areas next to the fence line are usually good for Golden-headed Cisticola as well as Red-browed Finch. The treatment plant is also a good spot for another grassland specialist, Tawny Grassbird. They have a particular preference for grassy around the northern-most out the back of the plant. The trees at the back of the ponds usually have a few Brown-backed Honeyeater, and you might see White-breasted Woodswallow, Leaden Flycatcher, Australian Swiftlet, and Red-backed Fairy-wren there also.

Finally, the treatment plant is an excellent spot to look for Fawn-breasted Bowerbird. They often hang around the trees outside the south side of the plant, flying from there across the road to the forest on the other side of Kuttini St. I also usually see, or at least hear (south towards Piiramo Rd.), Palm Cockatoo. Another bonus bird I have had at the treatment plant was seeing a King Quail, an uncommon bird on Cape York. There have been a few recent sightings there, so it is one to think about.

Quintell Beach (Lockhart River Beach)

Located 2 kilometre or so east of Lockhart River, Quintell Beach is a beautiful beach and a good birding spot. On the right side of the jetty, there are several large rocks in the water. These are good for roosting terns; I have seen Black-naped, Lesser Crested, Greater Crested, Little, and Australian Tern. From the jetty here you can scan out to the Coral Sea, with a good chance of seeing the terns mentioned above as well as Great and Lesser Frigatebird and Brown Booby.

A walk down the beach to the right of the jetty is worthwhile. Once, a Lesser Frigatebird patrolled up and down the beach, continually flying just overhead. Perhaps surprisingly, Palm Cockatoos are regularly recorded at Quintell Beach.

If you feel inclined, you can actually drive north along the beach; the access road is north of the toilet block. Driving on the sand, you can drive north for a kilometre or so, until you reach an estuary. There is a good chance of seeing Beach Stone-Curlew up near the estuary, as well as Siberian and Greater Sand Plover, Pacific Golden and Red-capped Plover, Whimbrel and Eastern Curlew, Common Sandpiper, Grey-tailed Tattler, Red-necked Stint, Australian Pied Oystercatcher, and Eastern Reef Egret, and look out for Osprey, White-bellied Sea-Eagle, and Brahminy Kite.

Chilli Beach

Chilli Beach has the look of a wonderful tropical beach, with palm trees bordering the beach. It is an excellent place for terns; for instance, I have seen Black-naped, Bridled, Little, Australian, Lesser and Greater Crested Tern, and Common Noddy. That’s not a bad list! Out to sea, you can also usually find a frigatebird, with a chance of both Lesser and Great Frigatebird as well as Brown Booby and Wedge-tailed Shearwater. Aside from the beach, it is worth looking across to Ma’alpiku (Restoration) Island and Old Mans Rocks, ~700 m off the coast, for circling terns and seabirds. Ma’alpiku (Restoration) Island is also famous for its Metallic Starling. During the warmer months at dusk, large numbers of Metallic Starling flock off Chilli Beach, forming murmuration around the beach and the island. Ma’alpiku (Restoration) Island is also where William Bligh landed after being set adrift from the Bounty in 1789.

Just up the beach to the north, look for shorebirds around the pools near the rocky areas. This spot of good for Lesser and Greater Sand Plover, Pacific Golden and Red-capped Plover, Common Sandpiper, Grey-tailed Tattler, Red-necked Stint and there is a chance of Beach Stone-curlew. On the beach you will also usually Australian Pied Oystercatcher and Eastern Reef Egret, as well as the odd Little and Great Egret, while White-breasted Sea-Eagle, Osprey and Brahminy Kite patrol the waters just off the beach.

BTW, if driving Portland Rd at night (perhaps on your way back from the Portland Road township), look for Large-tailed Nightjar as they flush from the road, particularly near the intersection to Chilli Beach. On one night, I saw at least 10 Large-tailed Nightjar. It was also hard to avoid Cane Toads.

Lockhart River Road and the Airport

I have found one of the best ways to find Palm Cockatoo is to drive up and down Lockhart River Road, listening for their distinctive and very loud whistles. A particularly good spot for them is just east of culvert 500 metres east of the Lockhart River Airport turnoff, an area intermixed with rainforest and woodland. Here I have had some great views of them, particularly early in the morning, when small groups gathering out in the open in the taller trees. Some try to draw attention to their impressive radiating black crest, other engaging in playful antics, while another gave the perfect impression of a Black-eared Catbird. They can be wary, so limit any movement, such as lifting your binoculars up too quickly. The area after the culvert is also a good place to see Papuan Eclectus and Red-cheeked Parrot, Blue-winged Kookaburra, and Magnificent Riflebird.

Another surprise about driving along Lockhart River Road is the presence of wild horses; they are usually a rich brown colour and regularly feed on the grassy areas beside the road and around the access road to the airport and are an impressive sight!

If you are staying in the cabins at the Lockhart River Airport, there is a good chance you will see Fawn-breasted Bowerbird, who regularly visit the trees at the airport. Palm Cockatoo and Papuan Eclectus Parrot sometimes fly over the airfield, so keep your eyes open.

Out of interest, the Lockhart River Airport was originally set up as an American airbase during World War 11. At the peak of activity, as many as 7,000 servicemen camped along the road between Portland Roads and the Iron Range Airfield.

Greenhoose

If you are staying at Greenhoose, you can access the rainforest walk behind the accommodation. It can be good for Northern Scrub-robin, Azure, and Little Kingfisher (along the creek at the end of the walk), as well as Magnificent Riflebird, Noisy Pitta, Tropical Scrubwren, Frilled-necked and Spectacled Monarch, White-faced Robin, and there is a chance of Black-eared Catbird.

A good way to birdwatch at Greenhoose is to birdwatch on Lockhart River Rd. immediately in front of the accommodation. Birdwatching here is particularly good for pigeons, such as Pacific Emerald and Bar-shouldered Dove, Brown Cuckoo-Dove, Dove, Wompoo and Superb Fruit-Dove, and Torresian Imperial-Pigeon. Not bad. It is also good for kingfishers; you might see Yellow-billed (listen for their call), Forest, Scared Kingfisher, Buff-breasted Paradise-Kingfisher in summer, and Blue-winged Kookaburra. Other birds to look for include Papuan Eclectus and Red-cheeked Parrot, Oriental and Little Bronze-Cuckoo, Noisy and South Papuan Pitta (listen to them calling next to Greenhoose), Fairy Gerygone, Varied Triller, Rufous Shrike-thrush, Lemon-bellied Flyrobin, Black Butcherbird, Spangled Drongo, Grey Whistler, and Yellow-bellied Boatbill.

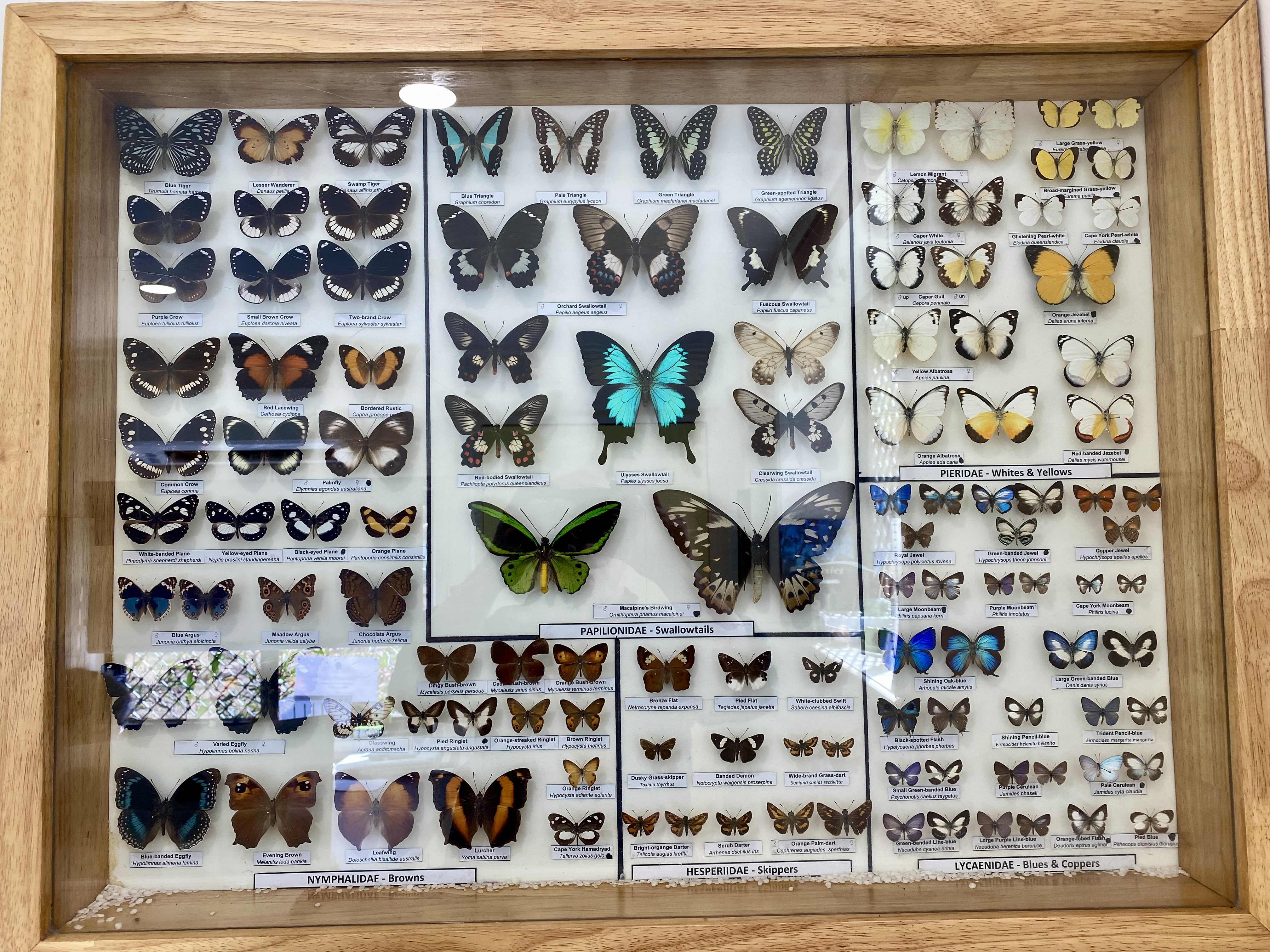

Greenhoose is a great place to see butterflies, who feed on the flowers in the garden. An estimated 223 of Australia butterflies are found in Cape York; that’s 60% of Australian butterflies. Indeed, the accommodation is regularly used as a base butterfly researcher; there has been some staying there nearly every time I have visited. Some of the butterflies to look out for include the majestic Ulysses Swallowtail; look for a wonderful series of bright blue flashes as it flies by. There is the equally majestic Cape York Birdwing (ssp. macalpinei), which looks very similar to the Cairns Birdwing. Other swallowtails include Red-bodied Swallowtail, Orchard Swallowtail, Fuscous Swallowtail, and, one of my favourites, the wonderful Clearwing Swallowtail, which supports remarkably transparent wings. You could also see Red-banded and Ornage Jezebel, Blue, Pale, Green and Green Spotted Triangle, Common, Purple, Small Brown, and Two-brand Crow, Palmfly, Red Lacewing, Cruiser, Shining Oak Blue, Lesser Wanderer, Glasswing (another transparent butterfly), Leafwing, Blue-banded Eggfly, and many more.

The White-lipped Tree Frog is also resident at Greenhoose, often hiding behind a picture or in a crevice. Australia’s largest frog, they reach up to 13.5 cm in body length. They are usually very green and, as the name suggests, have a white lip. After dusk, listen for their loud, harsh barking sound that I think resembles the quacking of a duck. Perhaps the most commonly heard frog in the rainforests of Iron Range is the Australian Wood Frog, particularly near waterways. On some nights they produced a cacophony of laughing squelching calls every night.

Ranger Station

Nearby, birding at the Ranger Station can be rewarding, particularly along the wall of rainforest north of the station—it is an area that is part of Greenhoose property. Look and listen here for Black-eared Catbird, Magnificent Riflebird, Noisy Pitta, and, in summer, South Papuan Pitta, who occasionally move out from the rainforest in the grassy area. There is also a chance of Fawn-breasted Bowerbird, and you might have flyovers of Palm Cockatoo, Papuan Eclectus and Red-cheeked Parrot, and Sulphur-crested Cockatoo. In the Iron Range, Sulphur-crested Cockatoo are usually seen as individuals or pairs, not flocks. In southern Australia, you would be hard-pressed to see Sulphur-crested Cockatoo in a flock under ten, and sometimes in the hundreds.

As a side note, it is worth noting that the rangers at Kutini-Payamu (Iron Range) National Park can be a little testy at times, particularly towards bird guides, so I recommend you treat them with great respect.

Coen

Just quickly, to finish off, before heading into Iron Range, you pass through Coen. On my first trip to Coen, we stopped to fix a flat tyre. I was surprised to find that the common town birds was Pied Currawong, This is the large-billed subspecies magnirostris; its distribution is limited to Cape York. Nice. Blue-faced Honeyeater was also common—again, another Cape York subspecies called griseigularis. It is some what smaller than other races. The common corvid for the area was the Torresian Crow. Coen had a nice feel to it, and it had some good shops. One shop in town had a pet Palm Cockatoo. Hearing for the first time made me jump! Palm Cockatoo! I rushed around to the back of the shop to look for it, only to find it was in a cage.

Preparation for my very first visit to the Cape York and Iron Range in 2009.